Drilling & Well Completion

Swab

Swabbing: A Powerful Tool in Oil & Gas Production

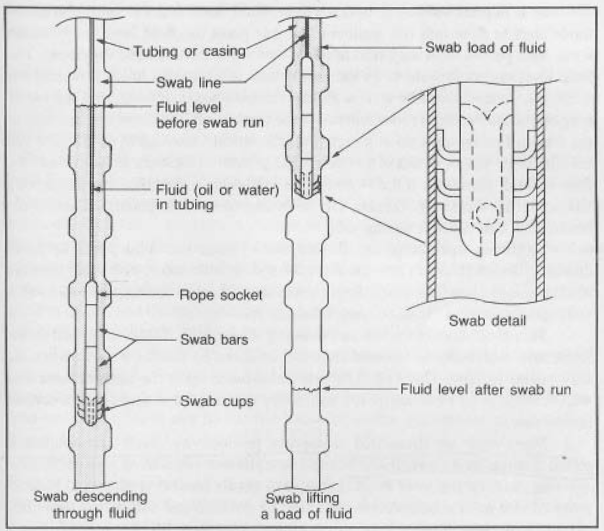

In the world of oil and gas extraction, "swabbing" refers to a technique used to manipulate well pressure. It involves rapidly moving a tool or equipment up and down the wellbore, creating a pressure differential that can be used to either remove fluids from the well or to help control well pressure.

The Mechanics of Swabbing:

Swabbing relies on a simple principle: the rapid upward movement of a tool within the wellbore creates a reduced pressure below the tool. This pressure difference can be harnessed for different purposes:

- Fluid Removal: By lowering a swab cup tool on a wireline into the well, then rapidly pulling it up, the reduced pressure below the tool draws fluids (oil, water, or gas) into the cup. This technique is commonly used to remove accumulated fluids from the wellbore, especially water, which can hinder oil production.

- Pressure Control: Unintentional swabbing can occur during the rapid movement of pipe or wireline conveyed tools, such as packers. This can cause a sudden drop in well pressure, which may be beneficial in certain scenarios but can also lead to instability or wellbore damage if not managed properly.

Types of Swabbing:

- Intentional Swabbing: This is typically carried out using a specialized wireline swab cup tool. The operator controls the speed and depth of the tool, allowing for precise fluid removal.

- Unintentional Swabbing: This occurs when equipment or tools are moved rapidly within the wellbore. Examples include running or pulling a packer, tubing, or other large-diameter tools.

Applications of Swabbing:

- Wellbore Cleaning: Swabbing can remove accumulated fluids, improving well production and reducing downtime.

- Water Removal: Swabbing is particularly effective in removing water from the wellbore, which can significantly increase oil production.

- Pressure Management: By strategically swabbing, operators can control well pressure, preventing surges or maintaining production levels.

Considerations and Risks:

- Tool Selection: The choice of swab cup tool depends on the wellbore size, fluid type, and production requirements.

- Speed Control: Too rapid a movement can damage the wellbore or cause equipment failure.

- Pressure Fluctuation: Swabbing can cause significant pressure fluctuations, which may need to be monitored and controlled.

Conclusion:

Swabbing is a versatile technique that plays a vital role in oil and gas production. By manipulating well pressure through rapid tool movement, operators can remove fluids, control pressure, and optimize production. Understanding the principles and risks associated with swabbing is crucial for ensuring safe and efficient well management.

Test Your Knowledge

Swabbing Quiz

Instructions: Choose the best answer for each question.

1. What is the primary purpose of swabbing in oil and gas production?

(a) To increase wellbore temperature (b) To stimulate the formation (c) To manipulate well pressure (d) To inject chemicals into the well

Answer

(c) To manipulate well pressure

2. How does swabbing create a pressure differential?

(a) By injecting fluids into the wellbore (b) By injecting compressed air into the wellbore (c) By rapidly moving a tool up and down the wellbore (d) By using a pump to circulate fluids in the wellbore

Answer

(c) By rapidly moving a tool up and down the wellbore

3. Which of the following is NOT a common application of swabbing?

(a) Wellbore cleaning (b) Water removal (c) Pressure management (d) Fracture stimulation

Answer

(d) Fracture stimulation

4. What is the primary difference between intentional and unintentional swabbing?

(a) Intentional swabbing uses a wireline swab cup tool, while unintentional swabbing involves rapid movement of equipment (b) Intentional swabbing is always performed by skilled professionals, while unintentional swabbing can occur during routine operations (c) Intentional swabbing is used to remove fluids, while unintentional swabbing is used to control pressure (d) Intentional swabbing is always planned and controlled, while unintentional swabbing is unexpected and potentially hazardous

Answer

(a) Intentional swabbing uses a wireline swab cup tool, while unintentional swabbing involves rapid movement of equipment

5. What is a potential risk associated with swabbing?

(a) Wellbore collapse (b) Equipment failure (c) Pressure fluctuations (d) All of the above

Answer

(d) All of the above

Swabbing Exercise

Scenario:

You are working on an oil well that has been experiencing decreased production. After analyzing the well data, you suspect that accumulated water in the wellbore might be hindering oil flow. You decide to use swabbing to remove the water.

Task:

- Tool Selection: Choose the appropriate swab cup tool for this scenario. Consider the wellbore size, fluid type, and production requirements. Justify your choice.

- Speed Control: Explain how you would control the speed of the swab cup tool during the swabbing operation to avoid damaging the wellbore or causing equipment failure.

- Pressure Monitoring: Describe how you would monitor well pressure during the swabbing process and what actions you would take if you observe significant pressure fluctuations.

Exercise Correction

**1. Tool Selection:** * **Choice:** A wireline swab cup tool designed for water removal, with a diameter appropriate for the wellbore size, should be chosen. * **Justification:** A swab cup tool specifically designed for water removal is ideal for efficiently extracting water from the wellbore. The diameter of the tool must match the wellbore size to ensure proper operation and prevent damage. **2. Speed Control:** * **Control:** The speed of the swab cup tool should be carefully controlled during the swabbing process. Start with a slow rate and gradually increase speed as needed, monitoring for any signs of pressure surges or equipment strain. * **Explanation:** Too rapid a movement can damage the wellbore or cause equipment failure. By gradually increasing speed, operators can observe the well's response and adjust the swabbing rate accordingly. **3. Pressure Monitoring:** * **Monitoring:** Well pressure should be closely monitored during swabbing using pressure gauges or other monitoring systems. * **Actions:** If significant pressure fluctuations are observed, the swabbing operation should be paused, and the well's behavior assessed. This may involve adjusting the swabbing speed, changing the tool, or taking other measures to address the pressure instability.

Books

- "Petroleum Engineering: Drilling and Well Completions" by John A. Davies and Michael J. Economides: This book provides a comprehensive overview of well completion techniques, including swabbing.

- "Reservoir Engineering Handbook" by Tarek Ahmed: This handbook covers various aspects of reservoir engineering, including well production and artificial lift methods, which often involve swabbing.

- "Well Testing" by John R. Fanchi: This book delves into the theory and practice of well testing, which can utilize swabbing techniques for wellbore fluid analysis.

Articles

- "Swabbing Operations: A Comprehensive Overview" by Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE): This article published by SPE offers a detailed explanation of swabbing techniques, applications, and considerations.

- "Swabbing for Wellbore Cleaning and Fluid Removal" by Schlumberger: This article focuses on the use of swabbing for wellbore cleaning and fluid removal, highlighting the benefits and challenges.

- "The Impact of Swabbing on Well Pressure and Production" by Oil & Gas Journal: This article explores the influence of swabbing on well pressure and production, providing insights into its role in well management.

Online Resources

- SPE (Society of Petroleum Engineers) website: SPE's website offers numerous resources on well completion and production techniques, including articles, presentations, and technical papers related to swabbing.

- Schlumberger website: Schlumberger, a leading oilfield service provider, provides information on their swabbing services and technologies.

- Halliburton website: Similar to Schlumberger, Halliburton offers insights into their swabbing services and equipment.

- Oil & Gas Journal website: Oil & Gas Journal publishes articles and news related to the oil and gas industry, including articles on swabbing techniques and their application.

Search Tips

- Use specific keywords: When searching for information on swabbing, use specific keywords such as "swabbing oil and gas," "swabbing well completion," "swabbing techniques," "swabbing equipment," etc.

- Combine keywords: Use multiple keywords together to refine your search, such as "swabbing pressure control," "swabbing fluid removal," "swabbing wellbore cleaning," etc.

- Include relevant terms: Include terms like "oil and gas," "well completion," "production," "artificial lift," etc. in your search to ensure you get relevant results.

- Utilize quotation marks: Put specific phrases in quotation marks to find exact matches. For example, "swabbing wellbore cleaning" will find pages containing that exact phrase.

- Explore specific website domains: Limit your search to specific domains, such as ".org" for organizations like SPE or ".com" for companies like Schlumberger or Halliburton.

Techniques

Swabbing in Oil & Gas Production: A Comprehensive Guide

Here's a breakdown of the provided text into separate chapters, expanding on the content where appropriate:

Chapter 1: Techniques

Swabbing Techniques in Oil & Gas Well Operations

Swabbing, a fundamental well intervention technique, involves the controlled vertical movement of a tool within the wellbore to manipulate pressure and remove fluids. The core principle lies in the pressure differential created by the rapid upward movement of a swab cup. This reduced pressure below the tool draws fluids into the cup, effectively removing them from the wellbore.

Several swabbing techniques exist, tailored to specific well conditions and objectives:

Conventional Swabbing: This uses a wireline-deployed swab cup with varying cup sizes and materials (e.g., leather, rubber, polyurethane) to accommodate different fluid viscosities and wellbore diameters. The speed and stroke length are carefully controlled to optimize fluid removal while minimizing wellbore damage.

Vacuum Swabbing: This technique utilizes a vacuum pump integrated into the swab cup, enhancing fluid removal, especially in low-pressure or viscous fluid scenarios. The vacuum assists in drawing fluids into the cup, improving efficiency.

Slickline Swabbing: Similar to conventional swabbing, but uses a smaller diameter slickline instead of wireline, allowing access to smaller diameter tubing and tighter wellbore sections.

Hydraulic Swabbing: This approach uses a hydraulically powered swab, often employing a reciprocating piston mechanism within the cup for a more powerful and controlled fluid extraction. It's suitable for removing heavy or viscous fluids.

Reverse Swabbing: This involves moving the swab downward to create a positive pressure pulse below the tool. This can be useful for pushing fluids down the wellbore or for dislodging blockages.

Each technique has specific operational parameters including stroke length, speed, and number of cycles, which are carefully adjusted based on factors like well depth, fluid type, and wellbore condition.

Chapter 2: Models

Mathematical and Empirical Models for Swabbing Analysis

While swabbing is a seemingly simple process, accurate prediction of its effectiveness and potential impacts requires sophisticated models. These models account for various parameters affecting fluid flow and pressure dynamics within the wellbore during swabbing operations.

Current modeling approaches include:

Empirical Models: These models are based on observational data and correlations, often developed from extensive field testing. They are relatively simple to use but may lack the accuracy of more sophisticated models for complex well conditions. They might correlate swabbing efficiency with parameters like stroke length, swab cup size, and fluid properties.

Numerical Simulations: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and finite element analysis (FEA) are employed to simulate fluid flow and pressure changes in the wellbore during swabbing. These provide more accurate predictions but require significant computational power and detailed wellbore geometry and fluid property data.

Analytical Models: These models use simplified assumptions and mathematical equations to describe the fluid flow and pressure behavior. They offer a good balance between computational cost and accuracy for certain well scenarios.

Future advancements in modeling will likely incorporate machine learning techniques to improve prediction accuracy and optimize swabbing operations based on real-time data from downhole sensors.

Chapter 3: Software

Software Applications for Swabbing Operations

Modern swabbing operations benefit significantly from specialized software applications designed to plan, execute, and analyze swabbing interventions. These software packages incorporate various models and algorithms to aid in decision-making and optimize operational efficiency.

Key features of such software include:

Wellbore Modeling: Visualization and simulation of wellbore geometry and fluid flow patterns during swabbing.

Swabbing Parameter Optimization: Tools to determine optimal swabbing parameters (e.g., stroke length, speed, number of cycles) based on well conditions and objectives.

Data Acquisition and Analysis: Integration with downhole sensors and logging tools to collect real-time data and analyze swabbing performance.

Reporting and Documentation: Generation of detailed reports and documentation for regulatory compliance and operational review.

Risk Assessment: Tools to assess potential risks associated with swabbing, such as wellbore damage or equipment failure.

Examples of software (though specific names would require further research as this is a niche area) might include specialized modules within larger well engineering software packages or dedicated applications for wireline operations.

Chapter 4: Best Practices

Best Practices for Safe and Efficient Swabbing

Safe and efficient swabbing requires adherence to strict operational procedures and best practices. This minimizes risks and maximizes the effectiveness of the intervention.

Pre-Job Planning: Thorough pre-job planning is crucial, involving detailed wellbore analysis, selection of appropriate swabbing equipment, and development of a detailed operational plan.

Equipment Inspection and Maintenance: Regular inspection and maintenance of swabbing equipment are essential to prevent malfunctions and ensure safe operation.

Proper Tool Selection: Choosing the right swab cup size, material, and type is critical for optimal fluid removal and prevention of wellbore damage.

Controlled Operations: Operators should strictly adhere to the pre-determined swabbing parameters to prevent excessive pressure fluctuations or wellbore damage.

Real-Time Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of well pressure, fluid flow rates, and other relevant parameters is essential to detect any anomalies and take corrective action.

Post-Job Analysis: A comprehensive post-job analysis should be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the swabbing operation and identify areas for improvement.

Emergency Procedures: Well-defined emergency procedures should be in place to address potential problems or equipment failures.

Chapter 5: Case Studies

Case Studies of Swabbing Applications in Oil & Gas Wells

(This section would require specific examples. The following is a template for how case studies would be structured.)

Case Study 1: Water Removal from a Mature Oil Well

Problem: A mature oil well experienced significantly reduced production due to water buildup in the wellbore.

Solution: Conventional swabbing was employed using a large-diameter polyurethane swab cup.

Results: Successful removal of accumulated water, leading to a significant increase in oil production. The case study would quantify the improvement in oil production rates.

Case Study 2: Wellbore Cleaning Following a Workover

Problem: Following a workover operation, debris and cuttings accumulated in the wellbore, hindering production.

Solution: A combination of hydraulic swabbing and conventional swabbing was used to remove the debris.

Results: Effective cleaning of the wellbore, restoring production to pre-workover levels. Quantitative data on debris removal and production recovery would be included.

(Additional case studies could focus on different well types, fluid characteristics, and swabbing techniques.) Each case study would detail the specific challenges, the chosen swabbing technique, and the quantifiable results achieved. This would provide valuable insights into the practical application of swabbing in diverse well scenarios.

- swab cup The Swab Cup: A Crucial Compo…

- Swab Valve Swab Valve: The Gatekeeper of…

- Application for Expenditure Justification Navigating the Appl… Project Planning & Scheduling

- Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled ("BCWS") Understanding Budge… Cost Estimation & Control

- Battery limit Understanding Batte… General Technical Terms

- DV Tool (cementing) DV Tool: A Crucial … Drilling & Well Completion

- TOC TOC: Understanding … General Technical Terms

Comments